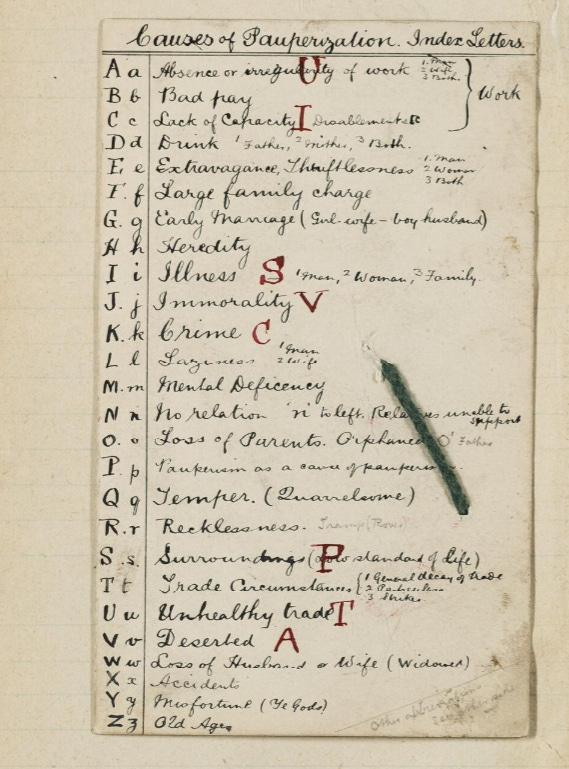

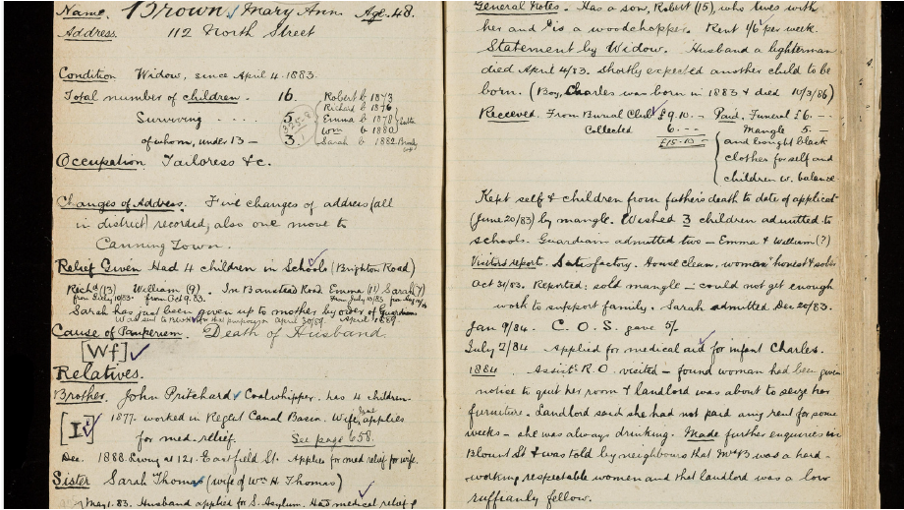

Today’s guest post is by Kerryn Krige, Senior Lecturer in Practice – the Marshall Institute, London School of Economics. What is social entrepreneurship?It is a question that scholars have been grappling with, eventually coming to the uneasy conclusion that there is no universal definition, nor should there be. If we are comfortable with our loose understanding of democracy, then we can be comfortable with a field that both lacks definition and boundaries. But this ambiguity is pronounced when you are teaching, facing a classroom of curious students who have all course-selected so that they can graduate with clarity on what social entrepreneurship is, why it is important and how to do it. Trotting out the patter that there is no definition and we must move on, doesn’t hold. And so, I began to search for another way for us to explore and understand what the “social” in social entrepreneurship truly means. Here, clarity emerges when we look to the past. In the late 1890’s industrialist Charles Booth and his small team of researchers started walking the streets of London, talking to policemen, publicans and religious leaders. They visited schools and workhouses, diligently transferring the notes made by administrators who captured the needs of people seeking help. Booth’s poverty maps are well known – and are very accessible through the digitised archives created by the LSE Library team[1]. But less well known are the Stepney Union case books[2] which record in short detail, the lives of people seeking help from the Charitable Organisation Society (C.O.S), a pseudo welfare agency, which decided who was worthy of receiving funds for essentials like food or medical expenses. Emerging through the texts is the competing narrative of poverty as a moral failing, a consequence of drink, laziness, extravagance and immorality, contrasting with poverty as the consequence of life events: a workplace injury, the death of a husband, sickness and old age. Booth, ever the researcher, created an alphabetised list of the causes of pauperism (poverty) which runs neatly through the case-texts. The case books allow us to explore what it is we mean when we talk about social change. The first entry in Notebook A (Booth B / 162) is for Mary Anne Brown, aged 48 who is again facing eviction after losing her husband. Mary is mother to 16 children, of which only 5 are alive at the time she meets the C.O.S administrators, including little Charlie, who is born after her husbands’ death. Captured in the Receiving Officers precise hand are the notes of Mary’s life – her efforts to get medical help for Charlie, her requests to have her children schooled. She tries to earn money, but eventually sells the mangle she bought with the insurance pay-out from her husband’s burial society. Her daughter Sarah, at age seven, is taken from her, to the Bromley workhouse. And then there is 3-year old Charlie’s death, on the 10 March 1886, and Mary’s request for money so he can be buried. Mary’s story allows us to see the devastating conditions of poverty, but also because of the timeline, to explore the underlying causes. What are the dynamics between power and authority that determine the life that Mary leads? What distinguishes poverty from inequality? Is our modern-day narrative of systems-seeking change, feasible when you look at the slow timeline of change? And are we guilty of continuing to moralise poverty, idolising self-sufficiency and entrepreneurial action as a redemptive pathway?

There are many benefits to using a historical lens in teaching social change. My top two are:

What the historical lens does is bring perspective. It helps us to understand complex, concepts, and to challenge the questions we ask. It helps us address our own moralising as social entrepreneurs, and to think critically about our cultural interpretations and motivations of ‘doing good.’ And the analytical distance that time brings allows us to see what is invisible, and through that build our understanding of the causes of things. With this, we can start building our understanding of what social change is, and how we approach our work, as social entrepreneurs. You can view a transcript of the entry of Mary Anne Brown here: [1] The LSE Booth archives are available here: https://booth.lse.ac.uk/map [2] Stepney Union Casebooks: https://booth.lse.ac.uk/notebooks/stepney-union-casebooks You're currently a free subscriber to Organizational History Network. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Friday, 14 November 2025

What is social entrepreneurship?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Biggest Workbook Ever For Autistic Families, Parents, And Carers

Pre-orders live now! ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

Online & In-Person ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

Dear Reader, To read this week's post, click here: https://teachingtenets.wordpress.com/2025/07/02/aphorism-24-take-care-of-your-teach...

No comments:

Post a Comment