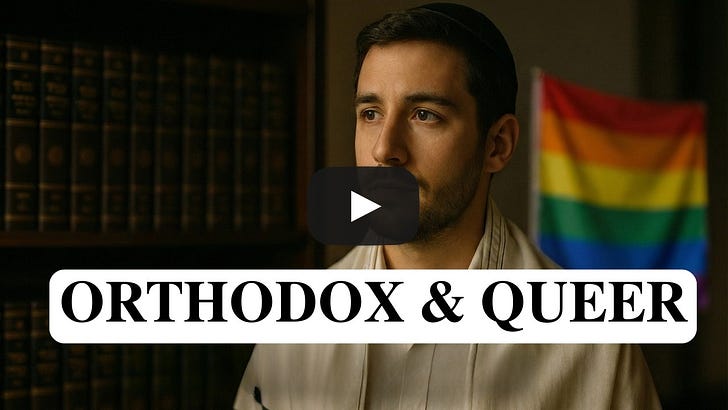

The Letters Will Become FacesRabbi Steve Greenberg on Tamar, Vayeshev, and the Future of Queer Belonging in Orthodoxy This week in Parashat Vayeshev we meet Tamar, a woman pushed to the margins of Judah’s family and forced to disguise herself just to claim a place in the future of Israel. When her story is finally revealed, Judah looks at her and utters the words that change everything:

It’s the moment when the tradition stops staring at law in the abstract and finally sees a human face behind it. Twenty-six years after Rabbi Steve Greenberg came out as the first openly gay Orthodox-ordained rabbi, that’s still the work: turning letters into faces. Steve once said that his willingness to be vulnerable to the Torah required the Torah to be vulnerable to him. If the people who interpret our texts truly heard queer stories, they might read those verses differently. So this week on Madlik, with Rabbi Adam Mintz and me, we ask: Are we entering a chapter where LGBTQ Jews are not merely tolerated, but embraced as teachers of Torah? Along the way we look at Tamar’s courage, the surprising flexibility of yibbum (levirate marriage), the paradox of chesed – kindness that sometimes overlaps with forbidden intimacy – and the Torah’s first truth about human beings:

We also touch on a striking new reality: in non-Orthodox seminaries, a majority of rabbinical students now identify as LGBTQ. What does that mean for the Judaism of tomorrow? Walking Into the Lion’s DenWhen I asked Steve to tell his story “al regel echad,” on one foot, he began not with theory but with Yom Kippur. For fifteen years he sat in shul on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, pulled his tallit over his head and quietly wept when the verses about forbidden sexual relations were read. It was the most painful liturgical moment of his year. Eventually, he says, he simply ran out of tears. At that point he did something that felt almost unthinkable: he asked for the aliyah to that very passage at Mincha on Yom Kippur – the day he calls “a death rehearsal” and a chance to square yourself with God. It felt like walking straight into the lion’s den. And yet in that moment, something unexpected happened. As the verses were read, a deep calm came over him. By not walking away from the text, by making himself vulnerable to it, he somehow demanded that the text respond to him – and to everyone like him. On some level, he felt, God did. It was the human interpreters, the rabbis, who weren’t yet up to speed. That experience launched a long journey of study: what might these verses mean if we took seriously the lives of gay and lesbian Jews who refuse to abandon the covenantal community? Tamar’s Fight to StayReading that story, I couldn’t help but think of Tamar in Vayeshev. Tamar is not simply angling for an aliyah; she is fighting for her life. Twice widowed by two of Judah’s sons, she is left in limbo, denied a future and a place in the family. Her response is as daring as it is desperate: she disguises herself as a sex worker and positions herself at the crossroads where she knows Judah will pass. Judah, for his part, responds to what he thinks is a roadside encounter with a prostitute. Behind the scenes, it’s almost embarrassingly simple: Judah is attracted to a woman he thinks is a harlot; Tamar is fighting to remain part of the people, to build a family and a future within the tradition that has nearly cast her out. When her pregnancy is exposed and she is brought out to be judged, Tamar doesn’t accuse. She simply produces Judah’s staff, seal and cord. Confronted with the story he never bothered to hear, Judah is forced to admit:

The midrash Steve and I discuss pushes this even further. Where the biblical text says Judah “did not know her again,” the rabbinic reading flips it: he never stopped being with her. Once you put a face to the verse, the meaning can turn 180 degrees! For Steve, Tamar’s story illustrates that the pathways to God’s will are not always straight lines. The Messiah’s lineage, he notes, runs through fractures and forbidden relationships that somehow become woven into the fabric of redemption. The question is: how do we build communities that remain deeply committed to tradition while making room for people who don’t obviously fit? “You Can Be Real About Who You Are – and Stay”Steve describes the quiet revolution among queer Orthodox Jews that he sees through Eshel, the organization he founded. There’s a new film, Holy Closet, which Eshel is helping to promote. It’s composed of short vignettes of queer Orthodox life: dating, marriage, children, ritual, community. The common thread is that these people are not waiting for official rabbinic permission to exist. They are choosing to retain their faith and commitment to halacha while building lives of love and partnership, even when the answers are partial or contested. Steve contrasts this with the older patterns:

Now, he says, more and more people are claiming a different path:

That insistence – that demand to be part of the system even when the pathways are unclear – is generating real change, in North America and in Israel alike. Bottom Up, Top DownRabbi Adam Mintz asked whether this is a product of a broader shift: are communities generally becoming more “bottom up” and less top-down? Steve thinks that in some sense it has always worked that way; it just wasn’t acknowledged. Rabbis have long known they cannot portray either God or themselves as absolute dictators. They have to make Torah livable for people they actually know and love.

But he agrees that something new is happening. People now have “Google rabbis.” In the age of Zoom and online learning – especially after COVID – people no longer depend on one local rabbi for all religious authority. They can seek out teachers and communities that meet them where they are. Steve performs same-sex commitment ceremonies (he is careful to say they are not kiddushin in the technical halachic sense), and Orthodox families show up, dance, and celebrate. They are no longer waiting to ask “is this okay?” before they show up for people they love. Twenty years ago, he says, even ten years ago, this simply wasn’t happening. Adam notes that he saw something similar around conversion during COVID: if one rabbi said no, a would-be convert could simply find another. Authority has been quietly dispersed. At the same time, Steve sees a surprising number of queer people seeking Orthodox conversion. Something in Orthodoxy – its seriousness, its discipline, its intellectual and spiritual rigor – draws them. They want a tradition that can face complex questions and still remain committed. Why Stay Orthodox?I push the question more sharply: if this is a community that, at least formally, rejects you – why stay? Steve’s answer, echoed by the people Eshel serves, is disarmingly simple: because it’s theirs. It’s my Shabbat, my Pesach, my community. You don’t get to tell me I don’t belong here. People are showing a Tamar-like tenacity; they are as persistent as the daughters of Zelophehad, or any of the “outsiders” who demanded a place in the biblical narrative. It’s a profoundly bottom-up energy: an insistence that halachic and communal change begins with people who refuse to leave. When Rabbis’ Hearts BreakAdam then asks about the “top-down” side: has there been any movement within the rabbinic establishment? Steve says yes, because eventually rabbis hear stories. People come to them, cry, and open their hearts – and rabbis’ hearts break. They begin to realize they carry responsibility for real lives. He tells a powerful story about a former head of the Rabbinical Council of America. This rabbi explained that he tells gay people they must live celibate lives, and that his heart goes out to them. Steve proposes a role play: a 16-year-old named Gabe comes to the rabbi and says, “I know I’m gay. What does God want from me?” If you tell him lifelong celibacy is his only option, Steve points out, the message he actually hears is: you will never love, never dance with someone you’re passionate about, never be held when you are sad or sick, never share physical intimacy with another human being – because something is fundamentally wrong with you. The rabbi is horrified. “I’d never say that,” he protests. Steve gently replies: “You just did.” So Steve offered an alternative formulation. Tell Gabe: I don’t know why God made you this way or gave you such a hard life, but here is what I ask of you: keep 612 mitzvot and do the best you can. And when you come before the Heavenly Court, you will have a very strong argument. God is merciful; it will be okay. In the meantime, join my shul. Then Steve adds one more step. Tell Gabe: I am forty years older than you; I will likely reach that heavenly Court before you. When you stand there and explain that you kept the mitzvot but chose life and love rather than isolation, I will be standing behind you, cheering you on. The rabbi began to cry. Steve’s goal, he says, is to help rabbis feel the weight of responsibility for hundreds or thousands of people who want everything a religious Jew wants – Shabbat, learning, Yom Tov, family, connection – and who simply refuse to live alone. Unsustainable Laws and Zigzag PathsFrom there we widen the lens. Jewish law has always had to confront the limits of unsustainable positions. I raise the example of ribbit, interest on loans, described in highly charged moral language in the Torah. (see Ezekiel 18:13) Yet commerce had to function; rabbinic creativity bent the law into forms that allowed economic life to continue. In a similar way, I suggest, queer Orthodox Jews who persist in the face of rejection are often taking a harder, more sacrificial path than the rest of us. They walk a zigzag route where we might walk straight. In a very real sense, they may be holier than we are. Who are we, as institutions, to judge people who pay such a high price just to stay inside? I also mention a recent study reporting that in non-Orthodox movements roughly half of rabbinical school applicants now identify as LGBTQ. Rabbi Amichai Lau-Lavie, among others, sees this as deeply meaningful rather than accidental. These are people sensitized to suffering, perfectly suited for communal work because they know what it means to care, to notice, to build community intentionally. Their identities are not a side note; they are part of the program. Parents as Activists, Queer Jews as Spiritual EngineSteve confirms that Orthodox families with queer children are indeed rethinking what holiness looks like. Many parents not only continue loving their kids; they refuse to remain in communities that reject them. Loving your child but davening in a shul that erases them is untenable. So parents become activists, pressing shuls and schools to respond thoughtfully. He also speaks about the spiritual depth he sees in queer communities. When you don’t fit expectations, you are forced to ask all the big questions: Who am I? Where do I belong? What do I care about? When those questions meet a Jewish tradition that is noisy, argumentative, and full of possibility, many queer Jews think: I might be able to live here. That spiritual energy, he believes, already enriches the Jewish world and will increasingly enrich Orthodoxy. A community that says, “We have a vision for your life even if you are LGBTQ,” is responding to the whole human being. A community that only has a vision for straight people is, in his words, a club for straight folks. And no one really wants to belong to a club for straight folks. They want to belong to a shul filled with old and young, straight and gay, people of different colors and languages – a religious community where the whole range of human experience is present. Becoming Chabad, Not SodomAdam presses on a real fear: some people worry that if they open the doors too wide, their carefully defined club will disappear. How does Steve answer that? His answer: we all need to become a bit more like Chabad. He describes how a Chabad rabbi welcomed his own brother, who at the time did not keep Shabbat or kosher, with completely open arms. No one demanded a full halachic commitment up front; instead, they invited him into relationship, trusting that love and engagement might do their work over time. Today, his brother stands in a very different place than when they first met. An open tent, Steve says, does not mean no structure. It means recognizing that people fall in love with Torah and God at different speeds and in different ways. It is not about control; it is about discovery and passion. Avraham and Sarah open their tent to strangers; the people of Sodom bar their doors and mutilate anyone who doesn’t fit their bed. We are both a people with demanding commitments and a people charged with caring for every human being on the planet. The trick is to remember both truths at once. “The Jews Have Their Jews”I bring in a line from the Arthur Miller play “An Incident at Vichy”

It is a dark line, but it rings true. Every community has its own internal minority, the people it would rather sacrifice to maintain its comfort. In our moment, the Orthodox queer community holds up a mirror. They want families, Shabbat, community. They are willing to make sacrifices to have them. In many ways they embody classic Jewish traits: a persecuted minority with a stubborn loyalty to covenant and peoplehood. Right now, Steve does not perform same-sex kiddushin as such; he works within the halachic parameters that exist. But it is hard not to feel that something is shifting – that structures we once thought fixed may look very different a generation from now. Judaism has already seen major status categories rise and fall over time. The institution of kohanim is not what it once was; other structures have similarly evolved. We may be in the middle of such a moment now. Eshel: Retreats, Warm Lines, and Real OptionsBefore we close, I ask Steve to talk more concretely about Eshel’s work. He describes national retreats – queer Orthodox gatherings in Baltimore that bring together people from across North America for Shabbat, learning, and community. There is also a powerful parent retreat, where roughly 150 parents of queer Jews come together to support one another and figure out how to make the Jewish world safer for their children. Eshel runs support groups, conferences and retreats for queer people themselves, for parents, and for other family members. They maintain a warm line for people all over the world who are trying to put together their identities and their commitments. They have even surveyed hundreds of Orthodox rabbis and communities to help queer couples figure out where they can actually live, which synagogues and schools will receive them, and where their kids might go to camp. In short, Eshel is not an abstract advocacy group; it is a practical engine of survival and belonging. The Tailor and the SanhedrinNear the end of the conversation, Steve shares one more text that he clearly loves: a passage from Vayikra Rabbah about a tailor referred to as Daniel HaChayata. The biblical verse speaks of the oppressed who have no comforter. Daniel raises his hand and says he knows exactly who that refers to: mamzerim – people born of forbidden relationships. They have done nothing wrong, yet they are barred from fully joining the community. Who are their oppressors? Not some abstract enemy, but the Great Sanhedrin, who use verses from the Torah to exclude them from love, partnership, and communal life. In the midrash, Daniel imagines God ultimately comforting these people and eventually purifying all mamzerim in the end of days. In the meantime, the rabbis, taking his words seriously, begin to limit when and how the category can be applied and disclosed, to such an extent that in most cases it becomes practically inoperative. The striking thing is not only the content of Daniel’s protest, but the fact that the rabbis canonized it. They preserved a story in which a simple tailor calls them oppressors. Why? Because they knew it was possible to wield Torah – even with the best of intentions – in ways that cause harm. Responsible halacha requires us to notice when a verse that once served a good purpose is now causing damage, and to adjust accordingly. For Steve, this is a model for how tradition can and must respond to the real lives of LGBTQ Jews. The Torah can be used to oppress; it can also be read in ways that heal. The difference lies in whether we let the human story into our halachic thinking. And so he ends on a note of determined hope: the tradition already has some room for LGBTQ people; it will have more. The Letters Become FacesAs we wrap up, we promise to link to Eshel in the show notes and invite listeners to support their work. Steve shares his contact info and signs off with a warm “Shabbat Shalom.” Tamar stands at the crossroads, Judah’s seal and staff in her hands. Queer Jews stand in the aisles of our shuls, in our families, on our bimot, holding their stories and asking to be seen. Rabbis, parents, and communities are slowly, sometimes painfully, beginning to turn. The work now is what Steve named years ago and lived that first Yom Kippur aliyah: To be vulnerable to the text. To insist the text be vulnerable to us. To let the letters become faces. Sefaria Source Sheet: https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/691629 Eshel: https://www.eshelonline.org/ Listen on Spotify

|

Tuesday, 9 December 2025

The Letters Will Become Faces

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Biggest Workbook Ever For Autistic Families, Parents, And Carers

Pre-orders live now! ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

Online & In-Person ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

Dear Reader, To read this week's post, click here: https://teachingtenets.wordpress.com/2025/07/02/aphorism-24-take-care-of-your-teach...

No comments:

Post a Comment