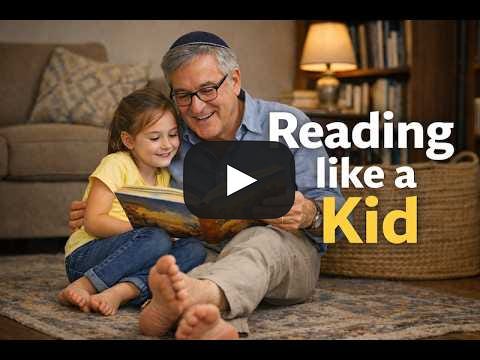

Every January gives us the same fantasy: this year we’ll read more. More books, fewer screens, fewer half-finished articles, fewer “I’ll get to it later” tabs. And then—almost mischievously—the Jewish calendar lines up with the secular one, and we open Sefer Shemot / Exodus right when we’re making resolutions anyway. So on this week’s Madlik Disruptive Torah, Rabbi Adam Mintz and I tried a different kind of New Year’s commitment: Read more Torah out loud—to our children, and (in our case) to our grandchildren. Because Exodus is Judaism’s most retold story. We read it every year at the Seder—arguably the longest-running book club in history. And the Torah doesn’t frame this as private spirituality. It frames it as intergenerational transmission:

Not once. Not “when they’re older.” Not “when they can appreciate it.” Tell it. Read it. Out loud. To help us take that seriously, we were joined by Ilana Kurshan, author of Children of the Book, who explores how reading to our children doesn’t only shape them—it reshapes us. And once you start thinking that way, Exodus changes. You stop reading it like a museum placard—ancient history, safely behind glass—and start reading it like a picture book on a living room rug. 1) Freedom begins with readingKurshan shared something that feels obvious only after you hear it: Her earliest memory of trying to read on her own wasn’t a children’s story—it was the Haggadah, the text we use to retell the Exodus each year. As a little kid, she wasn’t only hungry for the plot. She was hungry for the skill. Because she intuited that real freedom isn’t only “leaving Egypt.” Real freedom is being able to read the story yourself. That idea snaps the Seder into focus: yes, we tell the story about liberation—but we do it through a ritual of reading, interpretation, questions, and voices around a table. Even the verse that commands memory pushes it beyond a single night:

Exodus isn’t just a story we remember. It’s a story we keep re-reading until it becomes part of how we see everything. 2) “To your child” — and if you don’t have one, tell it anywayOne of my favorite moves on the source sheet is a line from Sefer HaChinukh on the mitzvah of telling the Exodus story. It notes that the verse says “your child,” but the obligation isn’t limited to literal parent/child. You tell it even to “any creature.” אֶלָּא אֲפִלּוּ עִם כָּל בְּרִיָּה That’s wild. And strangely beautiful. (and makes me associate with Maurice Sendak’s “Where the Wild Things Are”) Because it means the act of telling isn’t only about the listener’s age or comprehension. It’s about what happens to the teller when you tell it out loud. And that’s the theme Kurshan keeps returning to: Torah reading isn’t about logging books on Goodreads. It’s not “look how many I finished.” It’s connection. It’s relationship. It’s re-reading as a way of becoming someone new. 3) The burning bush: God chooses the one who stops and looksWe built a big chunk of the episode around the burning bush scene (Exodus 3), because it’s almost written like it’s begging for a child’s question: Why doesn’t the bush burn up? In the Hebrew, the language of seeing/re-seeing וַ֠יֵּרָ֠א pulses through the story—Moshe sees, turns aside to see, and God sees that Moshe has turned aside. After multiple references to seeing the story culminates with God syaing that HE too sees וַיֹּ֣אמֶר ה׳ רָאֹ֥ה רָאִ֛יתִי אֶת־עֳנִ֥י עַמִּ֖י Kurshan’s framing is sharp: God chooses Moshe not because he’s charismatic, or confident, or a natural speaker. God chooses Moshe because he notices when something is off—and he refuses to walk past it. That becomes a model for reading itself: Reading—especially reading out loud—forces you to slow down. And Ilana brings in a gorgeous Midrashic parallel: Abraham, walking past a “burning building,” asking: how can it be that nobody is in charge? In other words: Redemption begins with noticing. Noticing the bush. 4) Take off your shoes: reading as getting groundedWhen God tells Moshe:

Kurshan connected it to leadership—vision requires being grounded in the present. But it also landed for me in a more domestic key: Taking off your shoes is what you do when you enter a home. Holiness, in that sense, isn’t only Sinai… it’s on the carpet. It’s attention. It’s being fully there. 5) Picture books are MidrashOne of the most delightful “aha” moments in the conversation came from Kurshan’s example of The Seven Silly Eaters—a picture book where her daughter noticed something Kurshan herself missed: a cello that disappears for most of the story and returns at the end. Sefaria Kurshan realized: In richly illustrated books, the pictures aren’t decoration. They’re commentary. Illuminated, visual midrash—filling in gaps, answering questions the words never address. And that loops back to Exodus, where the text invites us not just to read, but to imagine—to build a world in our minds the way a child does naturally. 6) Words create miracles (Charlotte’s Web… and Torah)I didn’t have time to reference this in the podcast but Kurshan also brought in Charlotte’s Web—and the way a child can read it more theologically than an adult. In the story, the miracle isn’t lightning or magic. It’s language. A spider writes words. A farmer reads them. A life is saved. Kurshan quotes her son’s line (which is both funny and profound): Wilbur is saved because Charlotte is a good writer—with the right words, you can basically do anything. That’s not only a children’s literature insight. That’s Torah. God creates through speech. 7) “I’m slow of speech”: Moses as the child who doesn’t want to readThen we hit the moment where Moses refuses the mission:

This is Moses sounding like a kid at the edge of a page, terrified of stumbling. And God’s response is almost parental: I’ll be with your mouth. And when Moses still resists, God gives him a partner: Aaron. Kurshan connected that to a deeply contemporary parenting moment: one child flourishing, another child shutting down, and the realization that sometimes the loving move is to step back—and bring in someone else. In her case: grandparents, over video calls, reading together across an ocean. It’s one of those quiet revelations: Sometimes the way Torah gets transmitted isn’t a synagogue or a school. It’s a grandmother on FaceTime saying, “Tell me about your day. Take your time. I’m listening.” 8) Why we re-read: because we changeKurshan’s conclusion could be the mission statement for Torah itself: We re-read because the text stays the same—but the reader doesn’t. One year you read Rebecca’s pregnancy differently. Closing: Read it againExodus is the story we never stop telling. But maybe the deeper point is this: We never stop learning how to tell it. Sometimes we tell it like historians. And sometimes—if we’re lucky—we tell it like a kid on the rug, barefoot, looking up mid-sentence to ask: “Wait. Why doesn’t the bush burn up?” |

Wednesday, 7 January 2026

Reading Out Loud

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Biggest Workbook Ever For Autistic Families, Parents, And Carers

Pre-orders live now! ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

Online & In-Person ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

Dear Reader, To read this week's post, click here: https://teachingtenets.wordpress.com/2025/07/02/aphorism-24-take-care-of-your-teach...

No comments:

Post a Comment