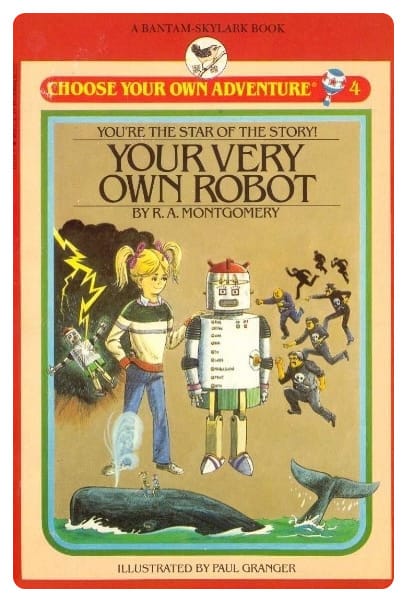

| It feels like university teaching is getting harder and harder. Less institutional support, more scrutiny from anti-intellectual reactionaries, student populations that are increasingly underprepared. And now, AI. We've had to deal with plagiarism since the origin of our profession. But with AI, our students have access to a machine that will create bespoke fake-erudite pablum on literally any topic for the mere asking. (You'll need to be a little more creative for it to provide instructions to make a bomb, though these robots are downright encouraging when it comes to self-harm, which is itself an actual public health crisis. Anyhow.) It wasn't that long ago when I wrote a book to advise fellow scientists about navigating common challenges in the classroom, but generative AI was not a thing then. So I am thinking of this post as an addendum for this moment in 2026. Teaching over the course of the semester is like one of those choose-your-own-adventure books. Every choice we make – and there are thousands of them that we make consciously and unconsciously – puts us on a trajectory into new territory. There are critical moments where our choices will send us down a totally different pathway. Like when you're on page 18 and choose "Offer the slice of gouda to the dragon," and then it asks you to flip to page 74. That's a whole new branch on the decision tree. When the AI issue comes up with our students every semester, how we choose to handle that moment will mark the trajectory of our relationship with our students for the remainder of the course. You could say that's the case for other decision points, but this one is a biggie because there are a lot of big feelings involving AI, and some of the key issues that get in the way of learning in college science classrooms all intersect with AI.  book cover of Choose your own adventure 4: Your very own robot. How about that! What are those key issues? The lack of kindness. Whether students feel prepared for the work. A lack of mutual respect. An adversarial relationship in which courses are obstacles and professors are the overseers. Far too many of us are quick to adopt that role as adversary standing between our students and the grades they want. What should stand in the middle is the academic challenge of the course, not the perceive caprices of the professor. It's hard to defuse that adversarial relationship when students walk into the classroom expecting things to be that way. But we still need to try. What principles should guide our choices? Ultimately, our decision needs to be rooted in our goals for the course, and more broadly, our purpose behind our choice to be in this line of work. When you think about whether you want to be a cop or a coach or a preacher or a buddy or a boss in the classroom, what's your motivation and what do you want for the students? Each one of those roles would handle student use of AI differently. We all should be coaches for our students learning. It's as simple as that. If you can envision yourself in this role, then all of a sudden some of these otherwise difficult choices get easy real quick. When I'm wondering what to do in the classroom, I think back to what is, ostensibly, the purpose of my course: to learn stuff. Not just any stuff, but the expected learning outcomes of the course. That's why we are there, and even if that's not the motivation of the students, that's what they signed up for. It would be great if students do other stuff along the way – career preparation, inspiration to go into research or policy work or teaching, a new best friend who happened to be in the same class, perhaps a professor as a valued mentor. That stuff is all gravy. The primary point of being there is to teach the content. I suppose there are some folks at SLACs with a more grandiose ideal of what we're doing on a day to day basis. I feel that way too a lot of the times, and frankly it drives my work to support the holistic growth of others (and myself just as much). But when we're deciding what to do in the classroom, let's not forget that we are there in the service of learning. We are there to teach, the students are there to learn. In other words: we are not there to grade our students like sides of beef, we are there to work with them as fellow human beings who are there to learn with our guidance. As a learning coach. Our employer and the broader game of higher education requires that our students receive a grade for being in the course, but assigning a grade is not the purpose of being there. The purpose is learning. The grade that students earn is the consequence of the learning process. If learning is the primary goal of the course, then we need to do things that promote learning, and stay away from things that get in the way of learning. You know what gets in the way of learning? When professors act like bosses or cops or judges. This AI situation is bringing out the worst in us. There are a lot of things about AI that can be true at the same time. It's a shortcut to getting work done. It might get the job done poorly, and sometimes it does it somewhere between adequate and spectacular. AI can be a cognitive shortcut that prevents us from learning how to do important things, and it also can provide shortcuts that get us right into the heart of what we are trying to learn. AI is a plagiarism machine, it's a masterful bullshitter, it tries to please you instead of challenge you. It also performs a bunch of rote tasks very efficiently so that you can spend your time on the part that requires human creativity and insight. AI is great at evaluation, but horrible at creation. Another thing is true: AI is here to stay. The financial bubble will pop and we'll be using it differently in the future, but it's futile to pretend that this isn't a tool that that will be involved in college classrooms. The whole AI-transforming-higher-education bandwagon makes me want to gag, but still I recognize that we have to teach differently now. And think that's a good thing. AI can get in the way of learning, and it can promote learning, depending on how it's used. I understand that we're dealing with a lot of cases where we are asking our students to do work independently, without the help of robots, because it is the process of the intellectual struggle that is required for learning. If you don't have to struggle, are you growing? So when students are taking the cognitive shortcuts that are harming their learning, what are we to do? First, always lead with kindness. Second, take steps to build and maintain mutual respect. Third, be good to yourself and don't do anything that makes your job harder than it already is. A friend of mine who teaches middle-school math has said, "Students don't follow rules. They follow people." (Did he come up with this? I have no idea, but I hadn't heard it before.) While we're teaching adults in college, I think this is a universal truth to a certain extent. I think it's true about professors who are going about their business on campus, for sure. Be the instructor who your students want to follow. So what does this kind, respectful, and not-additional-work approach to AI look like? First, don't go to any special length or effort to try to discern whether students used AI. It's not worth your time, and no matter what anybody might claim, you can't ever know for sure. Second, give students the opportunity to disclose whether and specifically how they used AI without any negative repercussions. (Not even a slant look askance.) Third, design your assignments so that students have the opportunity to learn what you want them to learn regardless of their use of AI. Fourth, design your assessments and your grading rubric to reflect what you want students to do and learn without AI. Build the circumstances, as reasonably as possible, for students to do this in a way that promotes their learning. If you need to grade differently because AI exists, then is it possible that your assignments and the way you were grading them weren't closely articulated to the learning objectives as they could have been? For example, if you're teaching biology, then it's never been a good idea to take off points for spelling. That's just punitive and makes students afraid and keeps them from focusing on the biology. We're not there to teach students to spell. Really – we are not. If they're in college and they can't spell words the way that they want to, that's on them at this point. There's no moral code or higher power that makes you the judge of proper spelling for fellow adults. You're there to assess learning in your discipline. The last thing I want to suggest about teaching in this new world where generative AI exists is that this provides even more incentive to shift towards assigning grades with a contract-based, specifications-based, or ungrading framework. If students can demonstrate certain competencies, or complete certain tasks to a certain level of quality, or provide evidence of the expected growth of learning throughout the course – all in ways that are clearly not done with AI – isn't that all we need to assign a grade? Let's not let this evolutionary arms race of avoiding cognitive work and detecting the lack of cognitive work get in the way of what we're doing in the classroom. Too often we let enforcement of arbitrary rules get in the way of learning. The more rules we make, the more we are going to have to enforce them, and the less focus that we can put on learning. |

No comments:

Post a Comment