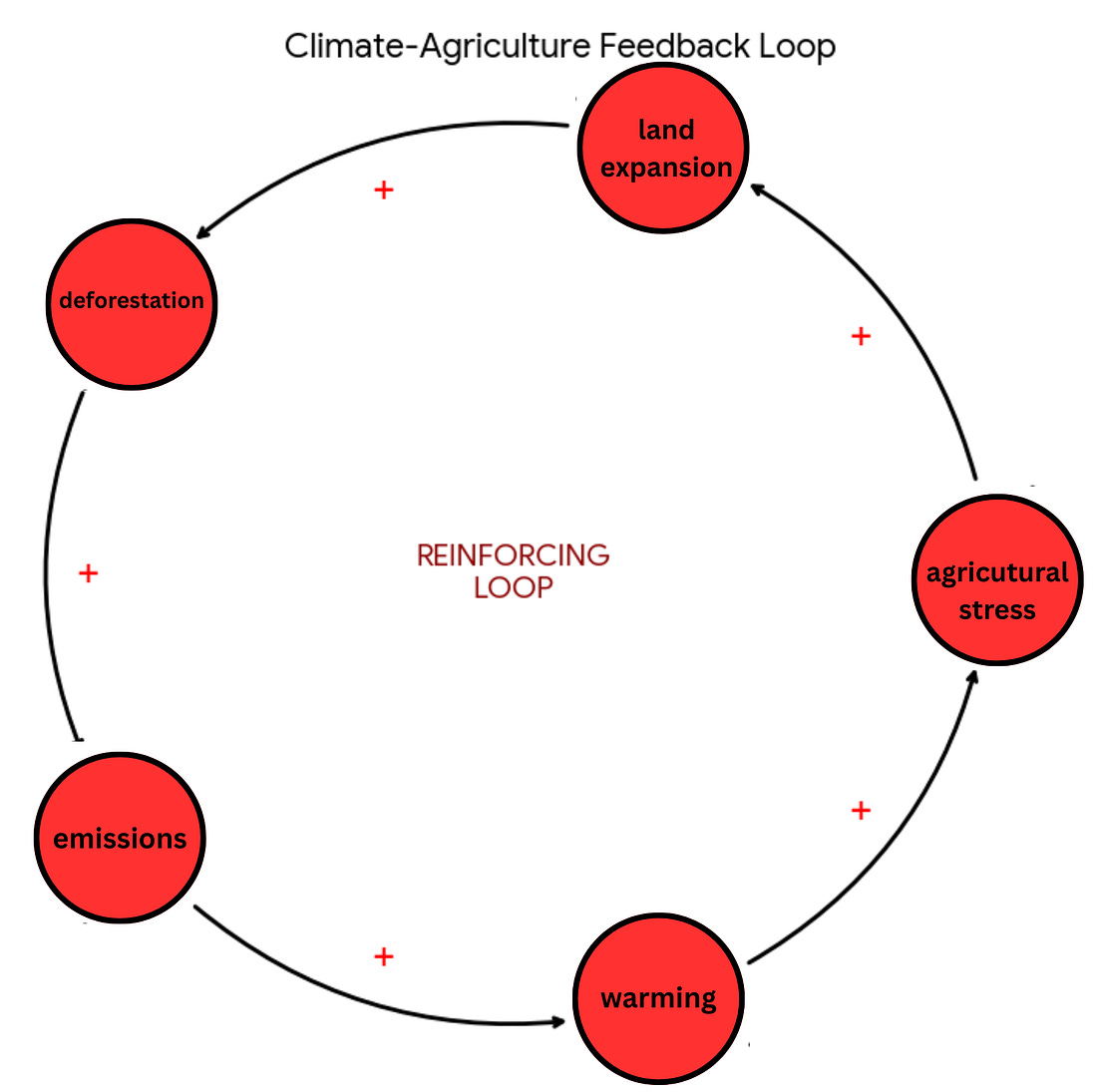

Growing enough food is a pressing concern in a world ravaged by the polycrisis. Agriculture is vulnerable to ecological stress, which decreases crop yields, drives up food prices, and threatens global food supply capacities. In 2025, this was evident in Brazil, southern Africa, and the western United States. Reduced agricultural yields from biophysical system breakdown also introduce risks into human systems by driving food insecurity, economic volatility, social unrest, and political instability. Current agricultural production is exposed to systemic, multi-layered risks (biophysical, economic, and geopolitical) that are intensifying and interacting. Three salient risks to agricultural production are soil degradation, climate change, and deforestation. Eroding topsoil is reducing nutrient retention, water-holding capacity, and microbial biodiversity. Soil is further degraded by fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation. Declining insect biomass also poses a risk as pollinators play a role in three-quarters of global food crops. Climate risks Global warming is reducing crop yields, diminishing livestock productivity, and driving price inflation. The cost of climate change-induced agricultural losses is pegged at $3.26 trillion over the past three decades and is projected to cost trillions more in the coming years. More than 10 percent of people are facing severe food insecurity, and 28 percent– nearly 2.3 billion people – are moderately or severely food insecure. An additional 600 million people are facing food insecurity by 2030. Reduced crop productivity is expected to cause an additional 500,000 adult deaths globally by 2050. Climate change adversely impacts agriculture in many ways, including extreme weather in the form of storms and floods that reduce harvested yields. One of the most common causes of crop failure is the growing frequency and duration of droughts, which increase water scarcity. Warming oceans and acidification are also decimating the habitats of marine life, which is a vital source of protein for billions of people. We are on track for at least 2–3°C of warming above preindustrial levels, which would subject multiple breadbaskets around the world to levels of heat stress that will diminish harvests beyond historical adaptation capacity. Warming of 2°C will drive down global caloric yields by 24 percent and cut the production of crops like wheat in half. Forests and Monsoons Forests are under threat from both global warming and agricultural expansion. We are cutting down forests to make room for more agriculture as we run out of arable land on which to grow food. Almost all our food comes from the small percentage of land that is suitable for agriculture. Removing forests threatens agriculture, as deforestation disrupts weather patterns that are essential for crops to grow. Tropical forests around the world are already perilously close to tipping points. Estimates suggest a dieback threshold for the Amazon between 2°C and 6°C of warming. The collapse of the Amazon would disrupt tropical monsoon systems through large-scale alteration of atmospheric moisture transport, surface energy balance, and land–atmosphere coupling. The consequences for agriculture would be severe and geographically widespread. The Amazon regulates climate and rainfall through moisture recycling (evapotranspiration/biotic pump mechanism). Vegetation releases water vapor and forms into atmospheric moisture streams that transport rainfall across South America. An Amazonian collapse would result in chronic drought caused by the breakdown of the South American Monsoon System. The Amazon also influences global atmospheric circulation. The collapse of the Amazon would also weaken West African and South Asian monsoons. Monsoons are foundational to food systems around the world, but especially in Asia, where more than 1 billion people depend on the Indian monsoon for food production. The Amazon is not just a regional ecosystem — it is a climate-regulating component of the Earth system. Its collapse could push South America toward permanent drying, destabilize global atmospheric circulation, disrupt multiple breadbaskets simultaneously, increase global food price volatility, and heighten political instability in monsoon-dependent regions. Amazon dieback is a potential climate tipping element with cascading impacts across hydrological, agricultural, and geopolitical domains. Conclusion The cascading effects of climate change diminish food production. To compensate for reduced yields, forest habitats are replaced with farmland, and this disrupts the global weather patterns essential to agriculture. Agriculture and climate change are locked in a reinforcing feedback loop, where deforestation is a corollary of reduced agricultural yields. This is a vicious cycle: Warming → agricultural stress → land expansion → deforestation → emissions → warming This reinforcing degradation loop links the food systems to climate change and forests. Agriculture is no longer merely adapting to climate change — it is entangled in a self-reinforcing Earth-system feedback that is eroding the very biophysical foundations on which global food security, economic stability, and political order depend. |

Wednesday, 18 February 2026

Agricultural Vulnerability

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

There Is No Such Thing as a Free Gift

Terumah, Purim, and the Language of Reciprocity ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏...

-

Dear Reader, To read this week's post, click here: https://teachingtenets.wordpress.com/2025/07/02/aphorism-24-take-care-of-your-teach...

-

CALL FOR APPLICATIONS: AOM 2025 PDW ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

No comments:

Post a Comment